Pablo Picasso. Personnage "Mousquetaire assis". 1972. Oil on canvas (69%)

New York, NY: Gagosian (Exhibition: Picasso: Tête-à-tête)

It would be madness to say that a late work like this one (year before he died!) is any legitimate good, but you'd also have to lie to say that it's fully impeachable. Forget the caricaturish eyes and nose and beard, forget the aqueous fingerpaint-y handling, forget the way the linework sits thick atop the picture plane like a bad burrito sits in your stomach. Look at that shard of grey nestled in yellow at the painting's left edge, and how it calls out to the embellishments on the musketeer's face and hands; look at the way the figure's right hand clutches that patch of color, which confuses our sense of what's behind and what's before anything in this picture; look at the depth that's created by the nose and the patch of green behind it leaning off in different directions from a shared point of departure. This thing's an ugly fucking mess, sure, but you can't say Picasso didn't know about design till the last. Even here, he manages to make space seem simultaneously undynamic and bursting at the seams.

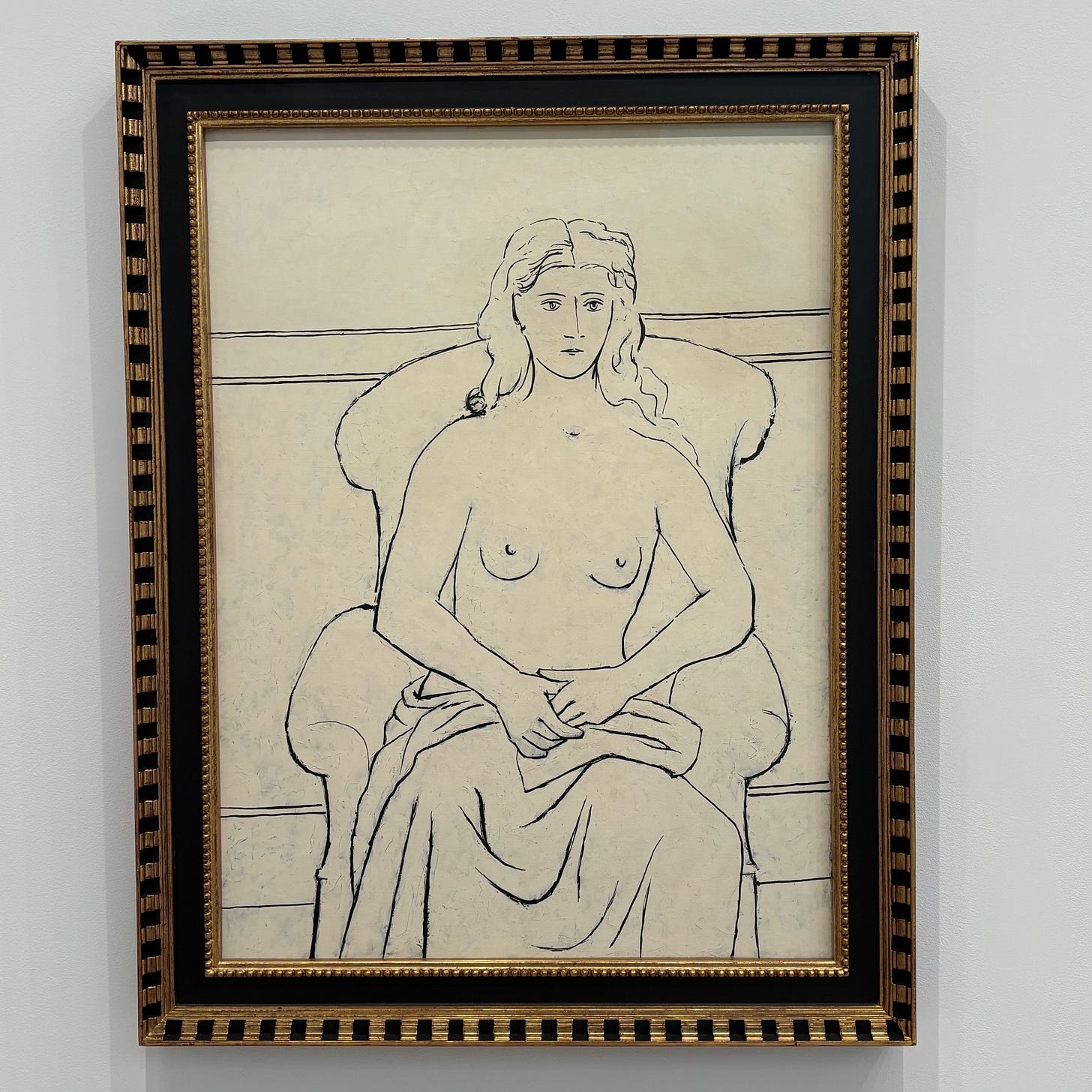

Pablo Picasso. Nu drappe, assis dans un fauteuil (Olga). 1923. Oil on canvas (88%)

New York, NY: Gagosian (Exhibition: Picasso: Tête-à-tête)

Picasso's "classicist" paintings can feel like bad rehashings of all the moves that led him to cubism, or they can feel like the craftsmanly calm after inspiration's storm. Seldom, though, do they feel like Nu drappe: an achievement of hard, unblemished design worthy of the artist's cherished Ingres, but also a painting that understands itself as a painting and — qua modernism — exhibits this understanding ceaselessly and destructively at every turn. For one, the way the room and the chair tilt one way and the sitter tilts the other as if she's been twisted out of position by some external force. For two, the contradiction between how supply every object's been limned and how flat the space between every line appears. For three, and most important, the vanishing palpability of the paint: it looks like there's a black underpainting over which the cream-white has been thinly layered, such that the picture's whole surface sort of vibrates with self-knowledge and potential while also serving as a perfectly neutral ground for the image. In this way, it's not at all dissimilar from the best portraits of Rembrandt.

Pablo Picasso. Maternité sur fond blanc. 1953. Oil on plywood (62%)

New York, NY: Gagosian (Exhibition: Picasso: Tête-à-tête)

It's well-known that Picasso spent decades in decadence, copying himself ceaselessly from his middle age to his death. The point of experiencing his late paintings, then, isn't to take them in as total artworks — they tend to be failures as totalities — but rather to pick them apart, to sift out their moments of inspiration, and to revel in what you can. Here, there's the red right arm of the girl (shouldn't it be yellow?), the sloping lap of her mother, the white space that's bracketed by breasts and arm, and the impossible flatness of the two hands on two shoulders. What do these amount to? Very little, especially given how visually commanding that spilled milk of a background is (it gets in the way, somehow, of any of these discretely charming passages coming together).

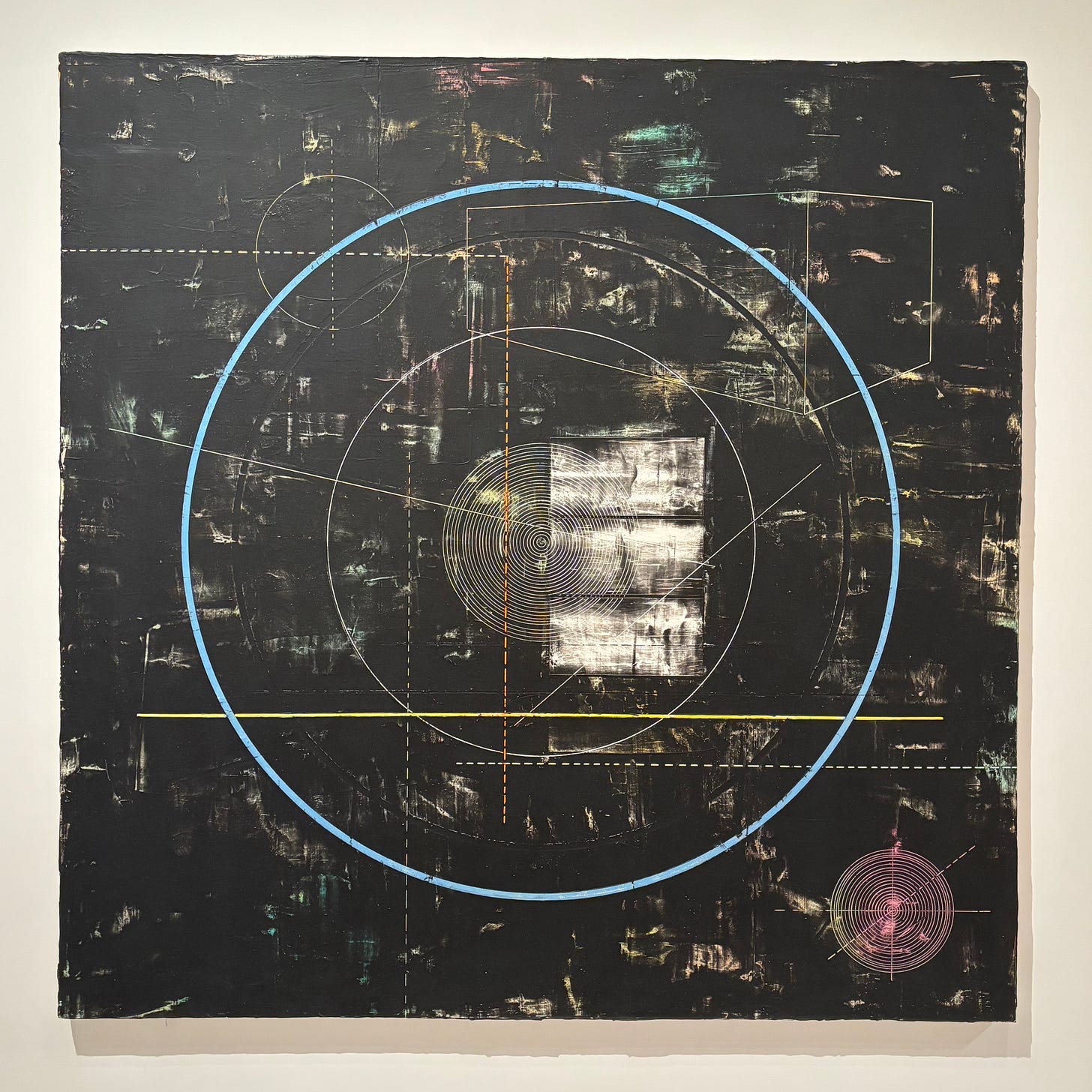

Jack Whitten. Dead Reckoning I. 1980. Acrylic on canvas (46%)

New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art (Exhibition: Jack Whitten: The Messenger)

Looks like a Torkwase Dyson, which is a bad thing. The linear, schematic elements seem to be lending order or structure to the black-and-colored miasmic field they're layered on top of, but without encroaching on the way in which that miasma struggles to make itself synonymous with the painting's surface. In other words, there are two mostly separate planes in this image, and both want to assert themselves as "figure" without becoming the other's "ground." It's a version of the same problem Whitten dealt with earlier in his career by, for instance, making palpable the objecthood of his canvases themselves, or by using odd tools to work up his surfaces so that so that the physical presence of his paintings would be nonidentical with the images it contains. These sort of "extra-painterly" approaches worked better for Whitten. This painting, to its detriment, is instead strictly pictorial. Its two layers are at once too alienated from each other and too imbricated to pull off the nonhierarchical figure-ground thing.

Jack Whitten. Pink Psyche Queen. 1973. Acrylic on canvas (75%)

New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art (Exhibition: Jack Whitten: The Messenger)

At his best — which is where a work like this one finds him — Whitten is an unrepentant late modernist trying mightily, à la Olitski or Ryman, to incorporate the idea and the essence of his paintings as objects into their effects as pictures. (Well, for Ryman it might actually usually have worked the other way around. But Whitten, unlike Ryman, is unambiguously a painter, not a maker of painting-objects.) In this piece, it's that strip at right of untreated canvas that does the work. But to reiterate, the upshot here isn't that the painting is thereby yanked out into the "expanded field" (or something like that) but rather that that edge becomes somehow pictorial — becomes incorporated into the coquetry of illusionistic depth that's going on on the painting's surface, between the pink haze and the heavy mess of color that's by turns beneath and blending with that pink. The bar of raw canvas ends up working pictorially in part because it amounts to a solid line, and there's hardly any linework in the painting-proper for it to be competing with. In part, it's because it's vertical against all the dragged horizontals to its right. In part, it's because it's not all that tonally dissimilar from the color’s main action. To the degree, however, that the unpainted strip is successful, it's also all a little disproportionate. One gets the sense that the whole of the painting is working for that band at its edge, and not the other way around. (Such disproportionality between parerga and the total work is present in much of Whitten's art.)